Location: Toronto, Ontario

Date of Completion: 2006

Architect: Architects Alliance with Behnisch Architekten

Nominated by: Jessica Bell, MPP (University—Rosedale)

Unlocking the advanced science of genomics requires flexible, technically advanced spaces that can host a diverse range of people and activities. Envisioned as both an instrument for science and a space for collaboration, the Terrence Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research (TDCCBR), part of the University of Toronto, is a leading example that cutting-edge science is as much about the human experience as it is about technology.

Front (southern) facade and forecourt. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Front (southern) facade and forecourt. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Built for the Pace of Science

Buildings dedicated to scientific research require frequent updates. After all, our probing and study of science must evolve alongside new discoveries and results, and laboratories must change and adapt to incorporate new technologies and needs. TDCCBR is no exception.

Running longitudinally through the middle of each floor is the key to the building’s adaptability for a variety of investigative methods: the service spine. By putting all of the building’s technical systems in an easily accessible and central location, it is possible for the university to quickly modify labs to suit the type of work being done—from a wet chemistry lab to a dry computer lab—without the need for invasive construction. Rather than a rigid and particular architecture, the TDCCBR provides a flexible and open scaffold for research, acting as a building-sized instrument for science itself.

However, providing the tools for science is only the first step. You also need to create spaces that support and enhance the experience of the people who will be carrying out the work. From computer scientists and engineers, to biologists and physicians, the building’s laboratories and collaboration spaces are made to host a wide variety of experts in bright, daylit spaces that encourage communication and collaboration.

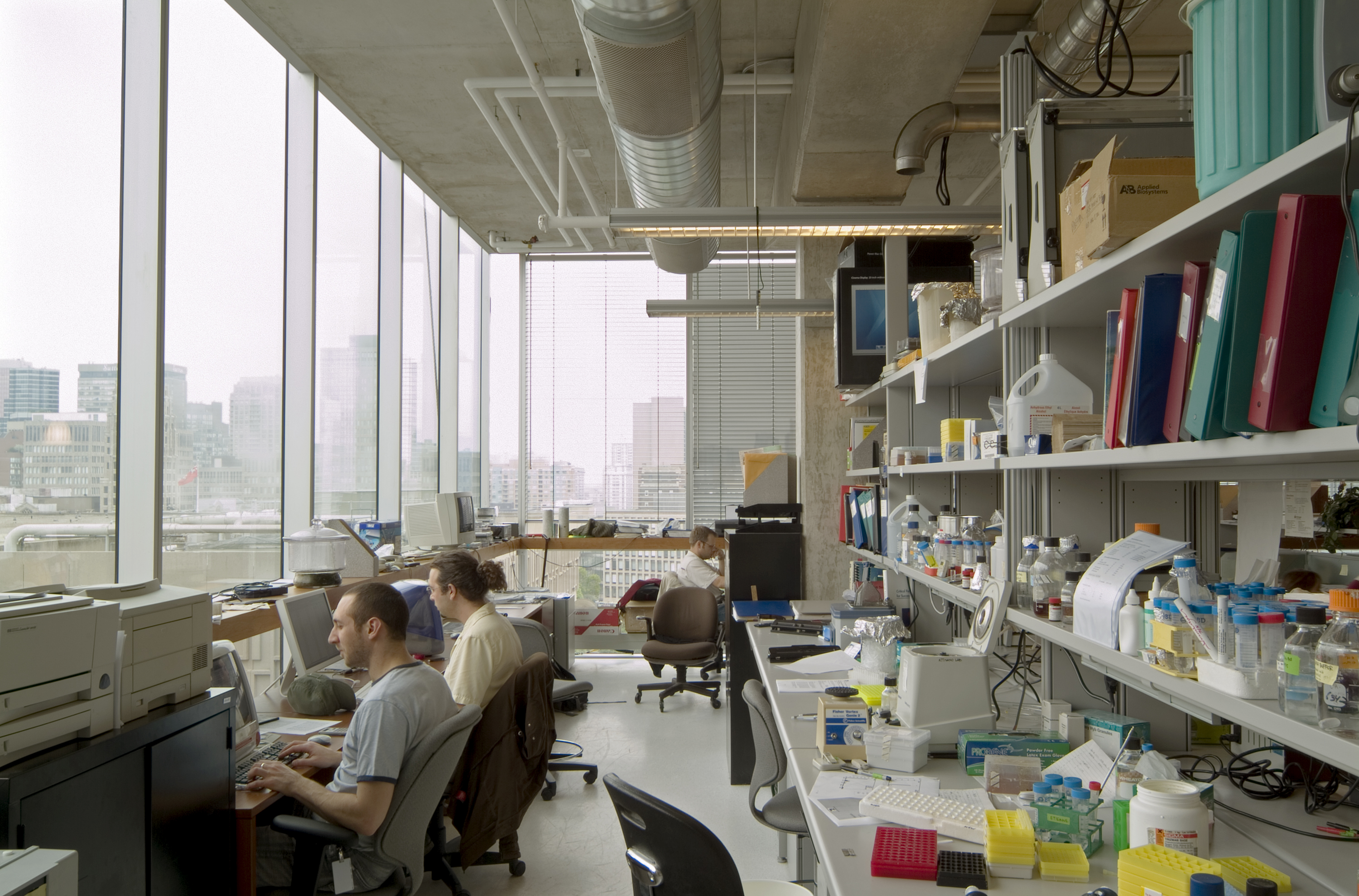

Light-filled laboratory and working space. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Light-filled laboratory and working space. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Each of the building’s 12 laboratory floors accommodates six principal researchers and up to 38 research associates. Double- and triple-height gardens located against the southern façade mediate the relationship between work spaces and the busy main street while also providing natural lounge areas for researchers to work and come together—a special advantage for the multidisciplinary research that the building hosts. “Write-up” spaces, directly adjacent to the labs line the eastern façade, providing expansive views of Queen’s Park and the city beyond. The result is a building built as much for technology as it is for collaboration and human comfort—all critical in our pursuit of scientific knowledge.

Double-height interior garden space. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Double-height interior garden space. Image courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Bringing the Outside In

Scientific facilities are often portrayed as fortress-like buildings, isolated from the context around them. The TDCCBR takes a different approach that embraces its role, and welcomes visitors and users from within the university and one of the largest hospital precincts in the world.

Flanked on either side by heritage-listed university buildings and featuring a generous plaza toward College Street, the Terrence Donnelly Centre was carefully designed to permit and encourage pedestrian flow through the structure and into the medical sciences building behind it. The plan of the ground floor—resembling that of an interior main street—makes little distinction between inside and out, maintaining an exteriority between the heritage façades, allowing them to retain their early 20th century expression. There is little ambiguity about what is new and what is old—a purposeful contrast that represents the immense progress made between then and now.

Plan of ground floor showing relationship to exterior landscape. Drawing courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Plan of ground floor showing relationship to exterior landscape. Drawing courtesy of Architects Alliance.

Granite paving on the College Street plaza continues into the Centre’s tall atrium and winter garden, punctuated only by colourful seminar rooms, circulation spaces, and eating areas. Open air walkways and stairs for the laboratories above look into the atrium, like balconies overlooking a street, accentuating the ground floor as an indoor/outdoor landscape. Plant selections ensure change between seasons, bringing dynamism and a connection to nature into the building’s interior. Informal wooden decks and benches hidden within the interior gardens create miniature parks that provide relief from the surrounding bustling campus. Even the interior lighting standards match those used outside, making a seamless indoor/outdoor connection.

These strategies serve to position the building as both an entrance into the University and a node in a network. It is not only a hub for academia, but also a place where ideas are applied and people are connected to the context around them.

This post forms part of our World Architecture Day Queen’s Park Picks 2023 series in which the OAA asked Ontario’s Members of Provincial Parliament (MPPs) to nominate a prominent building, past or present, in their riding for a chance to learn more about it. Check out the rest of the series to learn more about great buildings across the province!