Within the Toronto Public Library system, considered to be the busiest urban library system in the world, no library is bigger than the Toronto Reference Library. Completed in 1977 and designed by

Raymond Moriyama Architects, the library has become a Toronto architectural landmark and its rich history is a reflection of Ontario’s ever changing political and social landscape. It also illustrates the important role architects can play not only in the design of a building, but also in the site selection process and determining a successful programmatic mix.

The origins of the 1977 library date back to 1954, when Ontario’s legislature created the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, a second-tier municipality composed of thirteen cities. While libraries were originally left as local matters for each local municipalities to run and manage, in 1966 it was decided that a new library board was needed to bring together a number Central Libraries and other collections. In 1967 the Metropolitan Toronto Library Board was established, and by 1968 the board had decided that the origina

l 1909 Toronto Reference Library at St George and College, designed by Wickson & Gregg and A.H. Chapman, Associated Architects, would soon be unable meet the demands of the growing institution.

Before tackling any design considerations, the first question to be solved was where to locate Toronto’s new central library. The board wanted to ensure the new library would be easily accessible. They defined two main conditions for site selection: first, it should be within walking distance of Yonge Street and the subway, second, it should be somewhere between Queen Street and St. Clair. In 1971, the board requested Raymond Moriyama Architects to prepare a report evaluating numerous locations that fit their criteria.

After studying numerous sites, Moriyama reported back to the board with three main options: the northwest corner of Yonge and Asquith, just north of Bloor; the northwest corner of Yonge and Church; and the block immediately south of Eaton’s College Street, north of Gerrard. Given the confluence of the two subway lines, the site at Yonge and Asquith was seen as the obvious choice, and the board quickly authorized Moriyama to begin the design process.

Rendering of original proposal by Raymond Moriyama Architects, 1973.

On November 19, 1973, Moriyama unveiled his design. The proposed library was a five storey, 30,380 m2 (327,000 ft2) building completely clad in mirrored glass. The library would reflect its exterior during the day, and reveal its inner activity at night. The interior would be a large open space, with a tiered central atrium around which the collections and uses would be distributed.

While enthusiastically received by the Metro Toronto Council and the Metro Toronto Library Board, the library’s size, massing and exterior appearance met significant opposition at Toronto City Council, which had recently voted to prohibit any new project over 45 ft. high or 40,000 square feet. Responding to their concerns, Moriyama and the Metro Library Board worked closely with city planning staff and residents groups to figure out a suitable compromise. After four months of work a compromise was reached.

While the area was only slightly reduced and the building remained five storeys high, the exterior was almost unrecognizable. The building was changed from sheer walls to successively recessed tiers on both Yonge and Asquith, with the lowest tier at street level mimicking the height of the surrounding historical buildings. The building was also moved closer to the lot line, but arcades were provided along Yonge and Asquith and street-friendly programming such as an art gallery and a cafeteria were incorporated into the design to establish a more lively connection to the street. Among the most radical changes was the replacement of most of the glass with an orange brick facade, echoing the surrounding’s materiality.

As radically as the exterior had changed, the interior continued Moriyama’s initial concept as a tiered central atrium filled with plants and water features, reminiscent of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. A skylight would provide ample natural light into the space.

Photo Credit: Applied Photography Ltd, 1977. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

In April 1974, Toronto City Council finally approved the plans and by October 1977 the library was open to the public. When it opened, the library held 1.2 million books and contained 176 reading tables, 45 index tables, 62 audio carrels, 74 microfilm carrels, and seating for 420 in the meeting rooms and lounges.

The general openness and accessibility of the library’s design made it an instant success. Upon opening, the new Toronto Reference Library quickly became Toronto’s great living room, with its monumental yet inviting five storey atrium providing the perfect backdrop for research, study and play. The collection and programming was carefully laid out along the perimeter, with decorative ceiling banners hung in the atrium indicating the location of each collection.

Photo Credit: Applied Photography Ltd, 1977. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

In the early 2000s, after three decades of continuous use (not to mention radical shifts in the programming and technologies used in the library), the Toronto Public Library decided that a revitalization of the 1977 facility was in order. Leading this revitalization was

Moriyama & Teshima Architects, the successor firm of Raymond Moriyama Architects. The renovation and expansion of the existing building aimed to bring the library to the 21st century: both in terms of its social contribution to the city and in terms of its research and technological amenities. With the exception of an addition for event space at the back of the library, the interventions were all done within the existing framework of the building, respecting, preserving and restoring the essence of the architectural language already established.

Courtesy of Moriyama & Teshima Architects

In the interior, state-of-the-art design and technology has been incorporated into the Reference Library, keeping pace with emerging trends on how to process and make information. Innovative, custom designed study pods, learning labs and meeting rooms offer cutting edge technologies such as laser printers and 3-D printers, a Global Connect wall with individual listening domes; interactive learning touch-screens; a learning theater with high-tech projection, sound and recording features as well as wireless Wi-Fi and an abundance of power outlets throughout the entire building. The library’s stacks were also completely reconfigured, enhancing and simplifying the research process while encouraging enjoyment and discovery.

Learning Theatre, Photo courtesy of Moriyama & Teshima Architects

In addition to technological changes, diverse new social spaces were designed to accommodate different types of collaboration, including an expansive Event Centre to host major cultural and literary events; a Special Collections Rotunda that celebrates the library’s rich and varied collections and numerous Idea Gardens at various locations to encourage dialogue, idea exchange and community interaction.

The crown jewel of the library renovation is the Special Collections Rotunda which houses and showcases the wealth of the Toronto Reference Library’s collection in a unique space that is both highly visible and accessible. To protect the collection, the rotunda has been outfitted with an air-handling unit that works to control the environment inside the rotunda. The rotunda’s rich material palette - concrete, titanium and dark wood – is both modern and timeless, recalling the feeling of stately old libraries.

Special Collections Rotunda. Photo courtesy of Moriyama & Teshima Architects

From the exterior, one of the most noticeable changes is the new transparent glass entry vestibule cube which animates the street and showcases the interior activity of the busy library. A new library gift shop and café at street level act as welcoming and easily recognizable architectural features to this landmark building along its main elevation on Yonge Street. The cube recalls the original 1973 proposal presented by Raymond Moriyama.

Courtesy of Moriyama & Teshima Architects

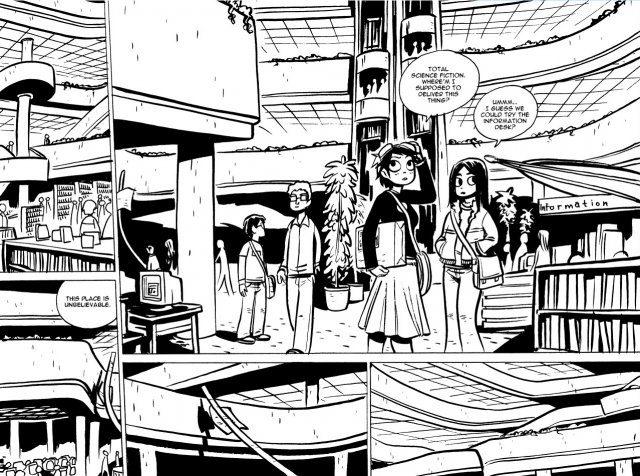

Almost four decades after its opening, the Toronto Reference Library is now deeply embedded into the architectural and cultural identity of the city. It has become a symbol for the city and a crucial public space for the larger Toronto community. In fact, it is so deeply embedded in Toronto culture that it is often found in the most unexpected of places. For example, in the pop-culture classic Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (Volume 2), the library’s celebrated atrium is the stage for an epic battle between Ramona and Knives Chau.

Want to know more about the building that housed the Toronto Reference Library’s unique collection prior to 1977? Then read our blOAAg post about the 1909 Toronto Reference Library at the corner of St George and College, designed by Alfred Chapman, in association with Wickson & Gregg. Sources

Want to know more about the building that housed the Toronto Reference Library’s unique collection prior to 1977? Then read our blOAAg post about the 1909 Toronto Reference Library at the corner of St George and College, designed by Alfred Chapman, in association with Wickson & Gregg. Sources Moriyama, Raymond. Metropolitan Toronto Library in Canadian Architect, January 1978, vol.23, no.1

Downs, Barry V. A Richness of Form, Space and Books in Canadian Architect, January 1978, vol.23, no.1

Calvet, Stephanie E. Moriyama & Teshima Architects Imagine and Re-Imagine The Toronto Reference Library, March 8, 2015, http://www.stephaniecalvet.com/stephanie-e-calvet-1/

Osbaldeston, Mark. 2011. Unbuilt Toronto 2: more of the city that might have been. Toronto: Dundurn Press.