“We are not committed to any particular style of buildings, but only to a certain spirit…. It is a spirit of appropriateness and beauty, which gives the kind of aesthetic stimulation and sense of repose which encourages scholarly application.”

Instructions to the architect, 1964

When it comes to Ontario’s libraries, few are as architecturally controversial as the Brutalist libraries of the 60s and 70s. Brutalism, a term originating from the French “béton brut” or raw concrete, was an architectural aesthetic and ethical movement with a strong emphasis on materials, textures and construction. Brutalism’s most characteristic material was concrete, often textured through board marking or pick-hammering.

Brutalism’s rise to popularity in Canada coincided with a massive government initiative to increase the offerings for higher education across the nation. As a result, many of Canada’s campuses, from Carleton University to Simon Fraser University, display a variety of Brutalist buildings. While Canada’s Brutalist buildings shares common characteristics such as heaviness, play with geometry, and use of exposed concrete, many of the most celebrated examples of this style are also heavily influenced by their site and other architectural styles.

Located on the southern edge of the Canadian Shield, surrounded by drumlins, rivers and elm trees, Trent University’s Symons Campus, master planned by Canadian architect Rom Thom, defies many of the stereotypes associated with concrete architecture. While Brutalist architecture has a reputation for being cold and detached, Trent’s campus is proof that Brutalism was also capable of architecture expressive of its place and ethos. Instead of feeling removed and austere, every building at Trent has been designed in dialogue with its natural setting, responding to the landscape and reflecting the school’s unique pedagogical philosophy.

Built between 1967 and October of 1969, the Thomas J. Bata library in considered by many as the most successful and beautiful of Ron Thom’s buildings at Trent. While sharing many of the characteristics of the Brutalist style, this iconic library also reflects Thom's Modernist sensibilities, marked by an interest in craft and attention to site and scale.

Bata Library over the Otonabee River, Trent University (Bata) Library, courtesy of Trent University Archives.

Jutting out over the west bank of the Otonabee River, the Bata library reflects Thom’s deep commitment in creating a meaningful relationship between built form and site. From the outside, the library’s relationship with the Otonabee is certainly picturesque, an effortless – yet overtly modern – extension of the site’s drumlins and limestone outcrops at the edge of the river. From the inside, the long windows provide occupants with uninterrupted views of the natural landscape.

The library’s thoughtful placement responds as much to natural conditions as it does to social intentions. Before its final placement, Thom diligently observed and studied the ebb and flow of the Otonabee to ensure many of the campus’s buildings were as close to the water’s edge as possible without placing the structures at risk. Socially, the founders of Trent envisioned the library as the most important hub of campus, the only building intended to be used by all members of this highly decentralized collegiate university. It was therefore imperative that the library be placed at the confluence of all pedestrian traffic, at the apex of two key walkways.

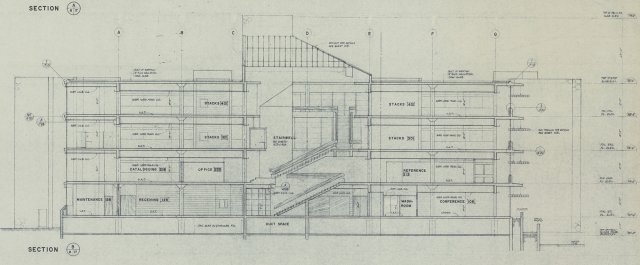

The surrounding landscape also played an important role in the library’s height. At four storeys tall, the Bata Library reaches the maximum allowable height under Ron Thom’s masterplan. Thom later explained that this particular height was chosen because it approximates the height of the predominant natural feature of the valley, its elm trees.

Rubbe aggregate concrete wall, Trent University (Bata) Library, courtesy of Trent University Archives. Photo credit: Yoshi Aoki

Even the walls of the Bata library reflect this profound relationship between building and landscape. Inspired by a visit to the then recently completed Morse and Stiles Colleges at Yale University (Eero Saarinen, 1959-1962), Thom requested structural engineers Yolles and Bergman to develop a method for construction based on rubble-aggregate concrete walls. These unique walls – a first in Canada – required large pieces of locally quarried limestone to be placed inside forms along with reinforcement rods. The forms were then pumped with a mixture of concrete and fly ash and allowed to set. When the form was removed, the concrete was scraped off by hand from the surface of the limestone to create a rough texture reminiscent of the natural outcrops of the campus.

If much of the building’s exterior responds to Trent’s natural setting, its interior and layout reflect Thom’s preoccupation with function and user experience. Originally conceived as a narrow curvilinear building, the library’s plan was redesigned to increase volume while minimizing its footprint. The resulting scheme is defined by one cube inscribed within another; the second cube rotated 90 degrees to create a building with eight corners.

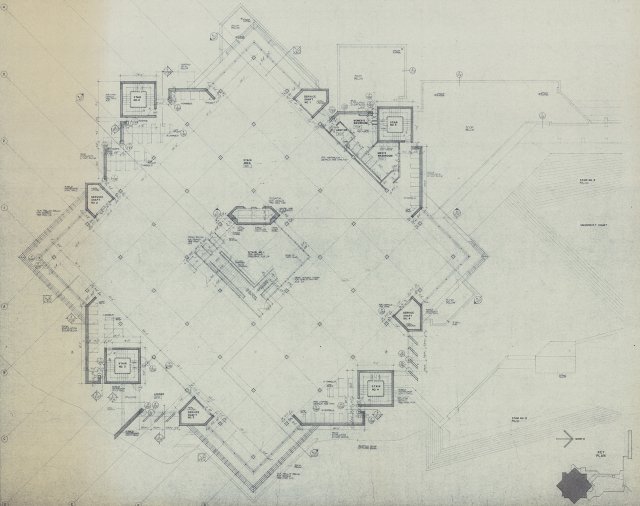

Third Floor Plan, Trent University (Bata) Library Project # THO 6406, Ron Thom fonds, Canadian Architectural Archives,University of Calgary

The interior is organized around a central light filled atrium, an important open space providing “a vital visual connection joining various parts of the library”. The second floor, at grade with the campus’s main exterior plaza, hosts the library’s main entrance and circulation desk. Above it, the third and fourth floors have been designed as library stacks, reading and study areas, and study carrels for graduate students.

Atrium, Trent University (Bata) Library, courtesy of Trent University Archives. Photo credit: Andy Turnbull

Section drawing, Trent University (Bata) Library Project # THO 6406, Ron Thom fonds, Canadian Architectural Archives,University of Calgary

Guided by a desire to create a

gesamtkunstwerk, a German word meaning a total work of art, Thom believed the architect should design, commission or otherwise oversee each and every component of the building, from the landscape to the furniture. The Bata Library is no exception, and Thom’s design team furnished the library with some of the most iconic furniture of the 20th century. Spouse and colleague Molly Thom managed the interior design component and was responsible for procuring Trent’s inviable furniture. Among the original furniture at the Bata Library we can highlight Swan chairs by Arne Jacobsen, Falkbenberg chairs, easy chairs and coffee tables by Muller & Stewart, and Diamond chairs by Bertoia. Thom also designed several custom pieces for the library, including rift-cut red oak study tables.

Special Collections Reading Room, Trent University (Bata) Library, courtesy of Trent University Archives. Photo credit: Yoshi Aoki

While the concrete architecture of the 60s and early 70s will remain a polemic and polarizing topic for the foreseeable future, the Thomas J. Bata library is a perfect example of how site and ethos can be embodied through a work of architecture. The library reflects Thom’s belief on the importance of design, no matter the scale. From the furniture to the masterplan, every element at Trent University is meant to stimulate and inspire students and foster a spirit of collegiality – all within the sheltering concrete walls of the mid-century campus.