Canada has a love for libraries. In Toronto alone, more people visit the Toronto public library system every year than the top ten most popular attractions combined – this includes Air Canada Centre, Rogers Centre, the CN Tower, the Toronto International Film Festival, and the Royal Ontario Museum. It seems fitting then that one of Canada’s most iconic buildings, closely associated to Canadian identity, is a library.

The Library of Parliament, designed by architect Thomas Fuller and his business partner Chilion Jones, is the only remaining piece of the original parliament building erected shortly after Ottawa became Canada’s capital in 1857. Referencing the medieval chapter house and with a layout resembling the then recently completed British Library Reading Room (Sydney Smirke, 1857), the Library of Parliament was the result of an architectural competition in 1859. Among the competition criteria, many of which are believed to have been written by Canada’s first Parliamentary Librarian Alpheus Todd, were the use of galleries and the need of fireproofing features.

The original Centre Block designed by Thomas Fuller and the Library of Parliament behind., c.1900. Source: William James Topley/ Library and Archives Canada / PA-009262

In keeping with the other buildings of the parliamentary precinct, Thomas Fuller designed the library in the High Victorian Gothic Revival style. The architect believed a “Gothic building only could be adapted to a site at once so picturesque and so grand”

1. Site however was not the only element influencing the stylistic choice. Two decades earlier, in 1834, London’s Palace of Westminster was lost to a great fire. When time came to build a replacement, there was significant public debate on which style to follow, the fashionable Neo-Classical style or the conservative Gothic. In the end, it was decided that a Gothic building was the appropriate stylistic choice to embody the British identity, and that Neo-Classical, which was common throughout the United States, had too many connotations of revolution and republicanism. When Fuller was laying the plans for Canada’s library of parliament in the late 1850s, the new Westminster Palace was beginning to approach substantial completion. It is not surprising then that the architect would select the Gothic style, the “true British style”, for Canada’s parliamentary buildings. This however, does not take away from the building’s Canadian identity, for it would be in the detailing and choice of materials that the library would distinguish itself from its European counterparts.

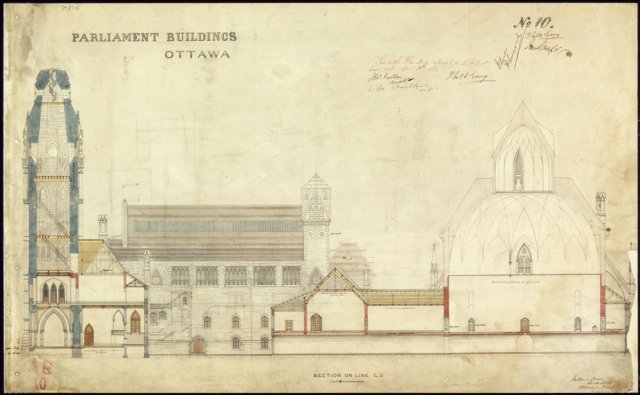

East and West elevations of the Old Centre Block and Library, showing the original two toned slate roof. Thomas Fuller, 1859. Source: Library and Archives Canada

The exterior of the library is defined by 16 massive flying buttresses and a colourful, rough stone exterior. A polychromatic façade, or multi-coloured exterior, is a key characteristic of the High Victorian Gothic Revival style. Four differently coloured stones were used for the exterior, all mined in Canadian quarries. Grey Gloucester limestone, grey Nepean, red Potsdam, and buff Ohio sandstone give the building a colourful yet unified appearance. In addition, purple and green slate originally covered the library’s tiered roof, but they were replaced by the now iconic copper after 1888 when a rare tornado removed much of the slate roofs of the parliamentary precinct.

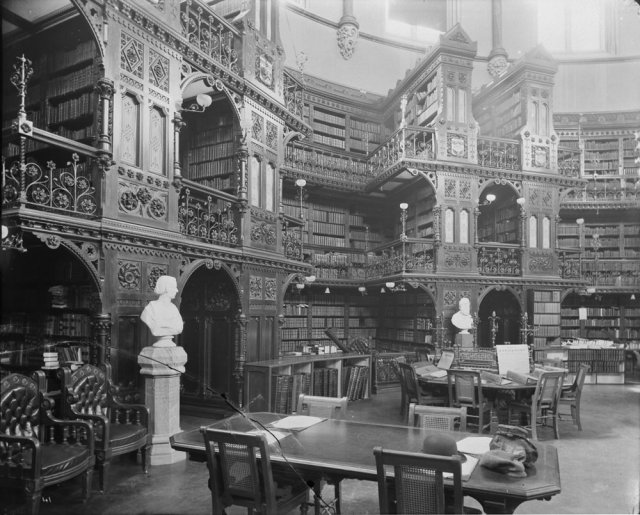

The attention to texture and colour continues in the interior, which has often been described as “the most beautiful room in Canada”. The circular room is lined with white pine stacks and galleries, carefully carved with thousands of patterns, flowers, masks, and mythical creatures. Prominently displayed around the room are the coat of arms of the seven provinces existing in 1876 and one for the Dominion of Canada. Above them rises a vaulted ceiling distinguished by brightly coloured and ornamented ribs and pilasters. It is said its circular shape and high ceiling were inspired by Parliamentary Librarian Alpheus Todd who recommended the building be “spacious and lofty”. Pointed arch windows and a brightly lit cupola provide natural daylight into the building. At the centre of the building is a marble statue of young Queen Victoria, sculpted by British artist Marshall Wood in 1871.

The library's interior in 1898. Source: William James Topley/ Library and Archives Canada/ PA-008375

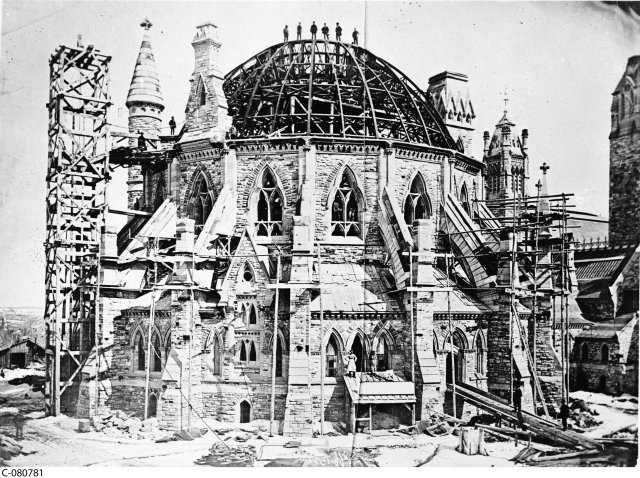

The library was also designed with a number of fireproof and fire retardant features. Its chosen location, slightly removed from the rest of the Centre Block and connected by a single corridor, minimized the risk of fire spreading from one building to the other. In addition, a heavy iron door separated the library from the connecting hallway. The roof was also designed with fireproofing in mind, specifying a wrought iron structure. The pre-fabricated roof was beyond the capabilities of Canada’s building industry and had to be made in Manchester by the Thomas Fairbairn Engineering Co. Ltd. It was state of the art at the time and it is believed that the library’s dome was the first of its kind in North America.

Section of Old Centre Block and Library, showing the connecting hallway between the two buildings. Thomas Fuller, 1859. Source: Library and Archives Canada

Pre-fabricated wrought iron dome being installed on the Library of Parliament. 1872. Source: Library and Archives Canada, Accession Number 1975-238NPC, C-080781

This attention to fireproofing would prove crucial on February 3, 1916, when a great fire consumed much of the Centre Block. The removed layout of the library, its incombustible stone structure, and the closing of its heavy iron doors protected the library from any damage, and today it stands as the only remaining part of the original 1860s parliament building.

Even with all the careful fireproof planning of Thomas Fuller’s original design, the library would eventually be affected by fire in 1952. The fire broke out in the cupola of the library itself, causing significant smoke and water damage. Following the fire, reconstruction efforts were led by Toronto architecture firm of Mathers and Haldenby, who replaced the original timber elements of the dome with steel and installed additional plaster fireproofing.

Like any building, the Library of Parliament requires constant maintenance to ensure its proper performance and longevity. In 2002, as part of a decade long conservation, rehabilitation and upgrade process, the library closed its doors for 4 years. Leading the work were four architectural practices: Ogilvie and Hogg, Ottawa;

Desnoyers Mercure & Associes, Montreal;

Spencer R. Higgins Architects, Toronto; and

Michael Lundholm Associates Architects, Toronto. Each firm provided a distinct skill for the project, working together to update and maintain this Canadian icon.

Ogilvie and Hogg managed the project. Desnoyers Mercure & Associes acted as the design architects, developing and implementing the heritage conservation strategy as well as the programmatic requirements outlined by the two remaining members of the architectural team. Spencer R. Higgins Architect had originally performed a preliminary historic building survey of the Library in 1990, and continued their research into the history of library as well as documenting the existing built fabric and consulting on a range of interventions thereafter–notably a new roof design. Last but not least, Michael Lundholm Associates Architects was responsible for interior planning and design of the library, including the architectural furniture in the Reading Room.

2 Thanks to these conservation efforts, today the library continues to offer information, reference and research services to parliamentarians and their staff, parliamentary committees, associations and delegations, and senior Senate and House of Commons officials. Through its services, publications and collections, the Library of Parliament tries to anticipate the needs of a busy Parliament. The library has become a symbol of Canada’s identity, featured prominently in postage stamps, souvenirs, and the ten dollar bill. Its design captures Canada’s journey in defining its own national character, with features referencing a strong British tradition and materials and details suggesting a uniquely Canadian identity.

References:1. Report of the Commission Appointed to Inquire into Matters Connected with the Public Buildings At Ottawa. 1863

2. Chodikoff, Ian. Parliamentary Briefing in Canadian Architect, September 1, 2006.