George H. Locke

Chief Librarian of the Toronto Public Library 1908-1937

Few names are as closely associated to the development of public libraries as the name of Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919). Carnegie, a Scottish-American industrialist who led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century, is best known for his philanthropic activities, including the funding of 2,509 free public libraries around the world. Between 1903 and 1922, 125 Carnegie libraries were built in Canada, of which 111 were built in Ontario. While the Carnegie libraries were not the first free public libraries in Ontario, they contributed significantly to the development of literacy in small communities across the province.

Administering the grant program was James Bertram (1872-1934), secretary to Andrew Carnegie from 1898 to 1914 and secretary of the Carnegie Corporation of New York from 1911 to 1934. He personally approved all the Ontario library grants, and would be responsible for the introduction of strict design and programmatic guidelines after 1907.

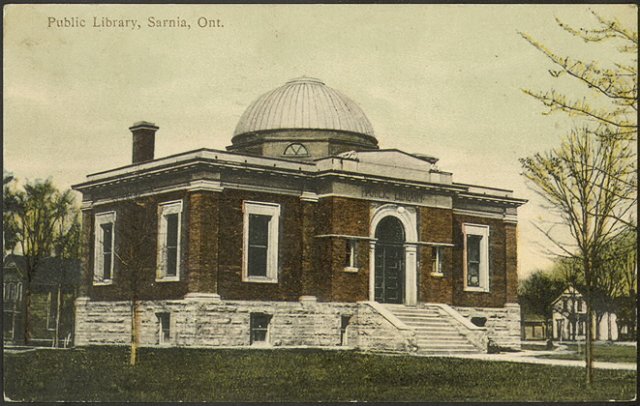

Sarnia Carnegie library (1903, demolished 1960), courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

Sarnia Carnegie library (1903, demolished 1960), courtesy of Toronto Public Library. Initially, Carnegie library grants only had to meet two conditions: that the community provide a site for the library, and that the City or Town Council should appropriate by taxation not less than 10 per cent of the cost of the building for annual maintenance including books and staff. Plans were never reviewed unless a request for an additional grant to complete the project was made. As a result, the libraries approved during this early period were more diverse in layout and style than their successors, and included features such as living quarters for the librarian, rotundas and large auditoriums which would later be barred by Betram.

While there were no strict design guidelines until 1911, many of Ontario’s early Carnegie libraries were designed with neo-classical features, with plans and elevations exhibiting Beaux-Arts theories of symmetry, sequence and classical detailing. This style had become the norm for important civic architecture across North America. Many of these early libraries were single storey with exposed basements, and featured a symmetrical elevations with large windows and centrally located entrances. In most cases the entrances were embellished with classically columned porticos, giving the libraries a sense of monumentality despite the modest scales. Some of the larger libraries, Sarnia, Guelph, Brantford, and Chatham, also prominently featured domes and rotundas.

Classical detailing continued into the interiors, where tall, plaster or pressed metal ceilings - 12-15 feet high -, decorated moldings, classical capitals, oak wood floors, and detailed brass grills played with the monumental exterior.

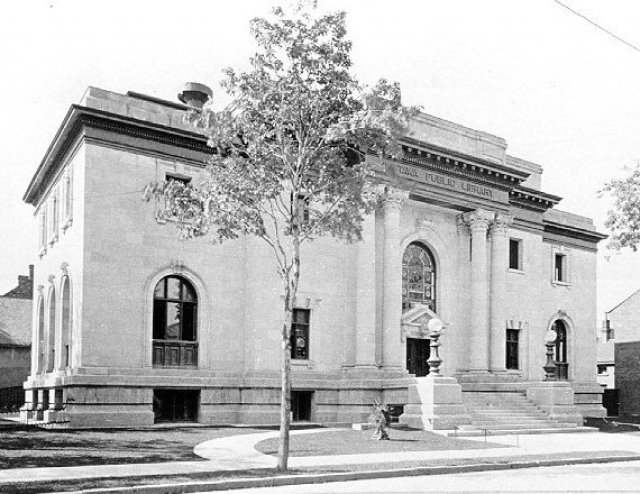

Ottawa Carnegie library (c.1905) featuring many Beaux Arts elements, Archives of Ontario, S=2047.

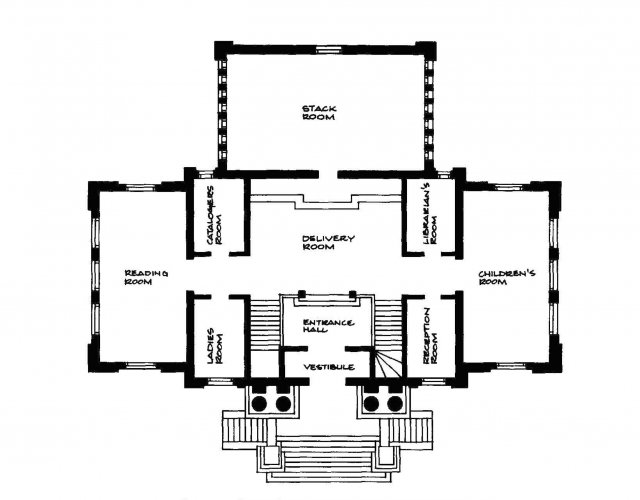

Ottawa Carnegie library (c.1905) featuring many Beaux Arts elements, Archives of Ontario, S=2047. In regards to layout, most of Ontario’s early Carnegie libraries featured separate stack rooms and reading rooms, allowing librarians to closely monitor and control access to reference material. A highly admired and copied floor plan was that of the Ottawa Carnegie Library (Edgar Lewis Horwood, 1906), known as the modified ‘T’ plan, which featured the desirable separate stack rooms. Separate rooms for men and women were also common in larger libraries; Berlin (Kitchener), St. Catharines, Waterloo and Brantford all featured this layout.

Ottawa Carnegie library (opened 1906), first floor plan, in The best gift: a record of the Carnegie libraries in Ontario.

While initially removed of planning and layout issues, James Betrand held strong views on what an ideal Carnegie library should look like. A strong believer of a simple-is-best approach, Betrand frowned upon excessive detailing and other features which he considered excessive and unnecessary. To him, a “Greek temple or a modification of it” was a cause of waste. He also expressed strong views against any element which he believed wasted space, always citing the ideal of “effective accommodation... consistent with good taste.” As the program progressed - and conflicts between architects, towns and Betram increased - Bertram increased the amount of supervision regarding the layout and planning of libraries. By 1907 he began requiring all libraries to submit plans and elevations before any grant would be awarded. In 1911, with the help of leading authorities from the American library and architectural professions, Betram produced a leaflet titled

Notes on Library Bildings, which was sent to all communities receiving a promise of funds from the Carnegie Corporation.

Notes on Library Bildings reflected many of Bertram’s ideals for the perfect public library. Specific recommendations included:

• A rectangular building

• One storey and basement, with outside staircase

• One large room subdivided by bookcases

• A basement four feet below grade

• Ceiling heights of nine feet for the basement and 12 to 15 feet for the main floor

• Rear and side windows seven feet from the floor to allow continuous wall shelving

• A lecture room as subordinate feature in the basement.

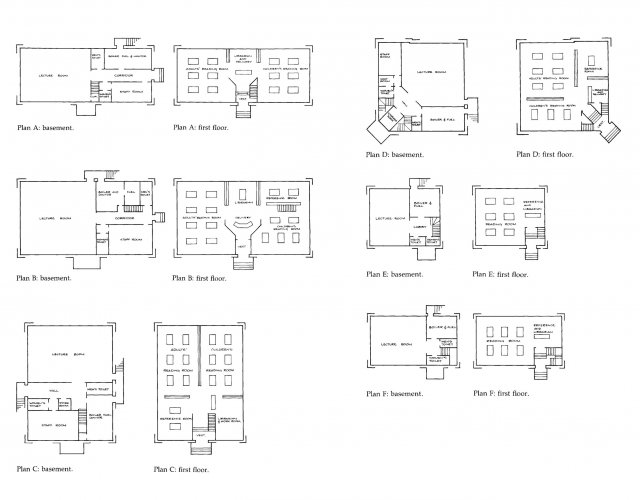

Notes on Library Bildings also included a series of plans, labelled A-F, which dictated the layout and placement of a Carnegie library at a variety of scales. Common among all plans was the use of book cases around the walls and the use of additional bookstacks for internal partitions and separation of functions.

Plans A-F, from Notes on Library Bildings in The best gift: a record of the Carnegie libraries in Ontario.

While the majority of Ontario’s Carnegie libraries pre-date the 1911 guide, there are notable examples of

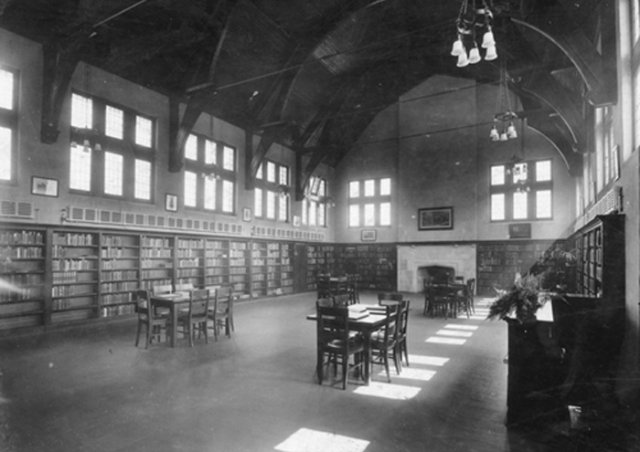

Notes on Library Bildings adhering architecture in Ontario, mainly in Toronto. The Wychwood Branch, Beaches Branch and High Park Branch libraries all follow an identical arrangement: a simple rectangular building, with an open floor plan and a symmetrical layout. Book cases were lined around the walls, while additional bookstacks partitioned the single large room and small reading tables were arranged as needed. The only two elements breaking the symmetry were the staircase and fireplace.

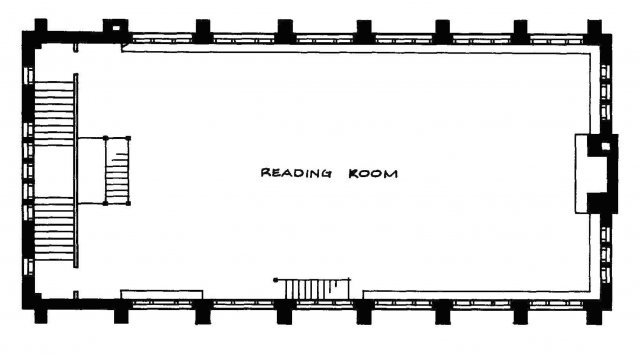

Above: Wychwood Branch (Eden Smith & Sons, 1916), 1st floor plan, in The best gift: a record of the Carnegie libraries in Ontario.

Below: Wychwood Branch library interior (Eden Smith & Sons, 1916), c.1916, courtesy of Toronto Public Library TRL T 12165

Ontario’s Carnegie Libraries are an important part of Ontario’s cultural, architectural, and civic heritage, reflective of the expansion of literacy throughout the province. Unfortunately, many Carnegie libraries have been significantly altered, with dropped ceilings, fluorescent lighting and painted woodwork diminishing much of their original character. Others, including the highly regarded libraries at Guelph and Kitchener, have been demolished. However, some of them still survive today with much of their heritage qualities intact. The Carnegie library at New Liskeard (now known as the Temiskaming Shores Public Library – New Liskeard Branch) has long been recognized for the preservation of most of its original features.