©2020, Ontario Association of Architects (OAA). Management of the Project articles may be reproduced and distributed, with appropriate credit included, for non-commercial use only. Commercial use requires prior written permission from the OAA. The OAA reserves all other rights.

Introduction:

This article is the second in a series to address the subject of Document Control. The series addresses the storage, retrieval, internal use and distribution of electronic information. The first article focussed on file naming conventions. This particular article (the first of 4 parts) deals with 'Internal Filing Systems' for external and internal documents in an architectural practice. The various documents being filed may be related to the management of the practice, the management of a project or to resource materials available.

The documents to be filed may be: 1) legal documents, financial documents, marketing materials; 2) drawings, specifications and related information such as is produced during the course of an architectural project; or 3) reference material, standards, and training material.

This Part 1 discusses the importance of having a good filing system, various components of a filing system and some principals/techniques for organizing files.

Background:

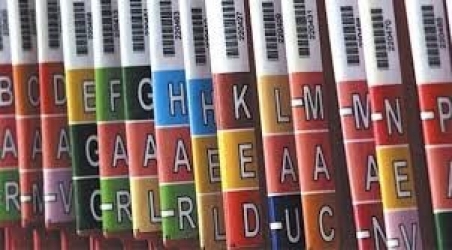

You may have grown up in the digital age, but most offices have been influenced by legacy systems that were developed before personal computers existed and which continue to exist because paper documents still exist. Before the digital age architects would use physical file folders, label them with the project name, number, and other information, then put them in a file or plans drawer or on a file shelf where administrative and project staff could access them. Sometimes access to the files was tightly controlled and in other cases anyone in the office could access the files.

In today's digital world the challenges of information management including its efficient retrieval, appropriate use, and distribution still remain similar in concept to the pre-digital era, but the format of storage has changed from tangible paper and mylar to intangible electrical charges stored in semi-conductors. From its inception to completion, the project’s information still has to be constantly received, distributed, organized and filed. A goal of any practice should be to streamline these processes so the information is reliably available when needed or else it can easily get out of hand with no one able to access appropriate files efficiently.

Regardless of how manual or automated a particular practice’s processes are, it is important for the practice to be able to access all documents whether project or practice related. The only reason to save/store/archive a document is to be able to access it later. If it won’t be needed later, don’t save it. If it may be needed later, save it so that it can be found again.

One way to accomplish this is to devise a hierarchical system that is reasonably intuitive and suitable for both physical and electronic documents. Another way is to use a non-hierarchical system with indexes and keywords that will retrieve documents for users without the user having to be concerned with where or how the document is stored. The former is suitable for a mixed physical/electronic environment. The latter requires a commitment to converting physical documents into electronic ones and the use of some software based application designed at least in part for document management.

Any filing system will need to provide a balance between a consistency in file classification and location from project to project over time (stability) so users can learn where different files are to be filed and where they may be found and the ability to respond to changing requirements without breaking completely (flexibility).

It is possible to strike multiple balance points between stability and flexibility and between complexity and simplicity. What you choose needs to work for your Practice and the way you do things. Often the choice comes down to personal preference rather than any technical superiority. If you don’t use it consistently, what’s the point of having a system. If your system is too complex, simplify it, then use it. If your system won’t accommodate your needs, modify it. You won’t get it right the first time, no one will, so don’t expect to. If you eventually do get it right, don’t expect it to stay that way. Technology and needs change, so expect your system to evolve over time. Think about what you need and what you want before you establish your system. You should then be able to tweak it as needed rather than scrapping it and starting over from scratch. This means that you should be able to find information in older projects almost as easily as in current projects.

The preeminent rule for using computers is to be consistent, even if you are consistently wrong. If you are consistent, then you can automate a change, a correction or a redirection. If you are inconsistent, you face a lot of manual changes/corrections.

One Filing System or Several

In any office there will be a need to file information for several different purposes. First are the files related not to a specific project, but to the management and operation of the practice as a whole (See Part 2). These include human resources files, customer relationship management data, marketing information, office and equipment leases, accounting information, etc. Second are the files related directly to the management of a specific project (See Part 3). These include drawings, specs, correspondence, work plans, schedules, agreements, etc. Third are the files considered as resources for multiple projects or as resources for staff (See Part 4), including training material, product literature, codes and standards, master specs and document templates, etc.

There is likely little overlap between the filing needs for projects, for the practice, and for resources. As a result, they may be treated as independent systems, linked only at the highest level in the hierarchy, if at all. You will need to decide on how to deal with the areas where overlaps do occur. For example, do the financial records for a project reside in the management of the project hierarchy or in the management of the practice hierarchy. Factors to consider include the requirements of any software used with the files, who needs access on a regular basis, and any security or privacy concerns.

There may be some groupings of folders that are repeated. For example a folder for green building systems having sub-folders for LEED, BREEAM, Green Globes, Passive House, etc. might exist in project folders to contain project specific information, in management folders for tracking membership, dues, and continuing education requirements, and in the resources branch to contain master templates, reference material, and training materials.

Hand written material or annotations on documents can be scanned and stored electronically, but not all items can be easily or adequately converted to an electronic format. Product samples and submittals are a good example. Thicknesses, textures and colour nuances may not be adequately captured by scanning or photographing a sample. As a result, even the most automated electronic filing system may need to accommodate physical files or storage boxes for some items. Generally, this will only need to be a small subset of the overall filing system.

Duplication of documents

Ideally, each document only exists in one location. Duplication of documents increases the cost of storage, creates ambiguity as to which copy is the latest, and ultimately may lead to the breakdown of any system of filing as people create copies in locations that may be convenient at the time for them, but which no one else would think of looking in for the file. When documents have a single defined location any annotations to a document will exist in only one location and there won’t be a need to check which copy was annotated or a need to check which every copy for annotations. One way to help achieve this is to use shortcuts/links to a single file location. It doesn’t help users become familiar with where documents should be, but it helps avoid duplication of files and the unintentional proliferation of multiple slightly different versions.

To reduce the desire to file multiple copies of documents, each document when created should deal with only one topic. If a document deals with multiple topics or issues, it makes it difficult to decide where to file it and may result in a separate copy being filed for each issue or topic.

Access control

Who has access to your filing system? (all staff, only staff working on a particular project or for a particular client, collaborators, project architects, partners, human resources, finance, clients) Do different groups need different types of access? (none, read-only, read-write, delete) How fine-grained do you need to be? (file by file, folder by folder, branch by branch). Addressing these issues may lead to a folder organization that organizes projects by client then by year, rather than by year then by project. You may end up with something like:

Server

\Client1 \Client2 \ Projects

\Projects \Projects \Year

This would allow access to Client1’s projects to be limited to certain staff, access to Client2’s projects to be limited to other staff, and other client’s projects to be accessible to all or to a third group of staff.

Organization

Are all the files related to a project located in the same branch with the project designation as the top level of the hierarchy or are the architectural files in one place, the marketing files in another, and the financial files in a third location?

Server1 Server2

\ Projects \Marketing \ Finance

\Year \Year \Year

\Project1 \Projects \Projects

Before you decide how to organize your files, consider not only what the file relates to, but who has to access it, how often it must be accessed, what security is needed, what software will be used to access/manipulate the files, and how the file/folder organization impacts back-up and restore operations and archiving.

Drive Mapping

It is most common on Windows based systems to map branches of the folder structure on a server to a specific drive letter so that the branch appears to be a physical drive on the system. This can be used to effectively disguise where in a folder hierarchy the files are by simplifying a folder structure to a simple drive letter.

This works reasonably well for practices with one office (the vast majority). If however, you have multiple offices and want to share file access or you want to collaborate with another firm or with other consultants on a project, you may run into problems with their files and yours having the same or conflicting mappings. For example if you both use P:\ for your own project files, what will you use for their project files? And if the software stores paths to reference files, will the paths work when it’s P:\ for one user and Q:\ for a user in the other office?

An alternative is to avoid drive mapping for any file locations that might be shared and to use URL’s instead. That way, no matter where a user is located, the URL and any stored paths are the same for everyone.

Sequencing

All computers have a default sort order used to display folders and their contents. It is usually based on the ANSI coding for the characters. The sort order is fundamentally alphabetical with numbers, punctuation, and other special characters fitted in. Since the sorting is done character position by character position, the default sort order can be unhelpful. It is common to add a prefix to file and folder names to impose a user determined order. The prefix is usually alphanumeric. Where it is numeric, use leading zeroes to pad numbers. Refer to the earlier article Electronic Project Document Filing Conventions for an example.

Chronological filing

Depending on the complexity of a project and on the amount of documentation being filed, it may be possible to file everything chronologically. This is straightforward and results in the most recent (and likely to be active) documents being quickly located. It does not help group documents by originator or by topic, and unresolved issues tend to get buried or scroll off the screen as newer documents are filed.

Another chronology based approach is to file documents by project phase. While this helps group documents, it requires judgement calls for many documents. If design development has been signed off on by the client and the project is officially in construction document phase, should a request from the client to change something in the DD drawings be filed under DD or under CD, and what do you do with design changes during construction?

Some information such as specifications may start during one phase and not be complete or final until the end of construction. This type of information may not be suitable for filing by phase. The best organization for such information may be to have a folder for the work in progress (WIP) (under development), a folder for the current version of the document (latest issued), and a folder for previous versions of the document (obsolete).

\Specs

\Architectural

\WIP

\Issued

\Archived

\Other

Filing by File Type

This organizational approach to filing was much more prevalent in the past when software was less interoperable and the file types for word processing, images, spreadsheets, and CAD could not be accessed or manipulated by a different application or application type. Now with software able to import and manipulate different types of information, there is an advantage to combining or mixing different file types in the same folders. This segregated approach may still be found for drawing files and for emails due in large part to the sheer number of files of these two types generated.

Filing by Originator

It may be effective to organize documents by who originated the document. This way you will have separate folders for each of the key stakeholders on a project. Within each folder, the files would by sorted chronologically or by topic. Where this organization isn’t helpful is in dealing with issues involving multiple stakeholders.

Filing by Key Event

There are a number of events or milestones that recur during the course of many projects. For example there might be folders for Site Plan Agreement, Permit Application, Tender issue, Contract Set, and each contract change document. These folders will contain a variety of file types from several different sources. This organization makes it easy to go back and look at what was issued at key points in time.

This ability to examine what was issued at any point in time may be enhanced by creating an archive folder for all key deliverables and saving a compressed file (ZIP) or a PDF or PDF/a file containing all the relevant documents while the original (editable) document files are organized differently.

Filing by Issue

During the course of a project many issues arise which may take time to resolve and involve documents from a number of different stakeholders. Filing all the documents including correspondence related to a particular issue is helpful in tracking progress, determining whose court the ball is in, reviewing the arguments being made and ultimately resolving the issue.

This is most easily done within document management software, which allows documents to be tagged and accessed by several different methods. It can be done manually, but you must then decide whether to duplicate the documents or to re-file them or not once the issue is resolved.

Correspondence

A significant amount of the material to be filed is correspondence of one form or another. One of the issues to address is whether to file the transmittal or covering letter with the attachments or separately. Another issue is where to file the attachments if they relate to several different issues or disciplines.

Ideally, each document only exists in one location. It is preferable to avoid duplication of documents. That way, any annotations to a document will exist in only one location and you won’t have to worry about which copy was annotated or which copy was later referred to.

Much of the correspondence generated these days comes via email and may be retained within the email system. Email systems are becoming more capable at filing and retrieving. Consider how and to what extent you will integrate your email and filing systems. If you retain attachments with the email, be mindful of the accumulative effect on the size of the mailbox as it will affect load and search times, and how long it takes to back up the mailbox. Since you perform daily backups (right?) and get emails every day, that single 14 MB attachment will get backed up every day. At the end of a year, it could be using up 5 GB of storage, and it won’t be the only large file that this happens to.

Software in use

The software that the office uses to run the practice or to execute the work on a project will have specific requirements that may impact your filing system. For example, the structure required to file all the components and support files for AutoCAD is very different than that required to store a BIM model.

It is important to consider that a project retrieved from archive at some point in the future may not be restored to the same drive designation or path or URL that it existed on originally. Have you chosen your software settings to accommodate this (e.g. absolute path vs. relative path) so that this does not make the files accessible but unusable without a lot of effort?

Does your file system accommodate your current software and is it flexible enough to respond to future needs?

In addition, some clients or project managers may mandate the use of their own project management software for tracking submissions, RFIs, and other correspondence to improve workflow by process automation. They have their own built in systems of organizing documents. Due to many new factors influencing the project delivery methods, internal filing systems in an architectural firm may have to adapt to or align with the method or software used by other stakeholders.

Where a practice is required to use software belonging to another party, the practice should still maintain their own system and file all of documents managed by the software separately. You may not have timely access or any access at all to documents stored in someone else’s system or in the cloud when you need it.

Back-up and restoration

How selective does your software allow the back-up and file restore operations to be? Is your file system appropriately structured to suit your back-up and restoration needs? Can you restore just the CAD or BIM files or just the contract admin files or do you have to restore an entire project. Different back-up systems allow selective back-up based on a variety of parameters which may look at file attributes, folder attributes or other parameters. Make sure your back-up system meets your needs.

Many have a rude surprise when they go to restore a project only to discover that the backups are corrupted in some way and won’t restore. When was the last time you tested your backup by actually restoring some files? This caveat applies not only to local or tape backups, but also to backups sent to off-site facilities. Until a file has been restored, it is not known if the complete process works as intended or advertised.

Archiving

No one has unlimited storage. Is your file system structured to allow you to simply archive entire projects or is it a complex time-consuming process involving files from several different branches on different servers?

Document files should always be current in their assigned folders. Only the most current document files should remain in the folders. The older versions should be promptly archived in a separate folder created at a suitable location.

Document retention

Different types of information must be retained for different periods of time. Most financial information will be retained for seven years to meet Canada Revenue Agency requirements. Many project files will be retained for 15 years in response to the statute of limitations. For some files the retention duration will be established in the project contract.

It may be helpful to group items with similar retention periods in the same branch or branches of the folder hierarchy to facilitate purging of information no longer required in order to reduce storage costs.

Obsolescence

As with any information stored in a proprietary or native file format, give consideration to how you will access the information if the software adopts a new file format, the software disappears from the market and is no longer available or the operating system changes and requires a different version of the software.

One partial solution to this is to archive files in a non-proprietary format (as a straight text or image file) or in a proprietary format that is supported by multiple software vendors (e.g. Adobe’s Portable Document Format (PDF)), and in particular the PDF/A variant. How appropriate this solution is will be determined in part by how much functionality is lost in the translation between formats and by how valuable that functionality is.

Another aspect to consider is physical obsolescence. The industry has moved through a succession of common media (8” floppy, ¼” cassette tape, 5 ¼” floppy, 3 ½” floppy, compact disk (CD), digital video disk (DVD), USB ram drives) as well as less common proprietary solutions using disk or tape, each with several variants in capacity requiring different hardware. Each of these media types have their own durability issues and each requires the appropriate hardware to read and restore the files. Do you still have access to the hardware and operating systems needed to restore your files?

Summary

No file system is or ever will be perfect. The details will change over time as the software you use changes and as project or office needs change. Expect to revise your file system, adding some folders or branches and deleting/pruning others. A well-considered file system which responds to the organizational principals referred to in this series of articles should be flexible enough to accommodate such changes without destroying the overall structure.

These articles do not represent OAA policy or guidance but rather are based on the opinions and experiences of members of the OAA and are prepared for the benefit of the profession at large.

Updated: 2020/May/06